Menu

close

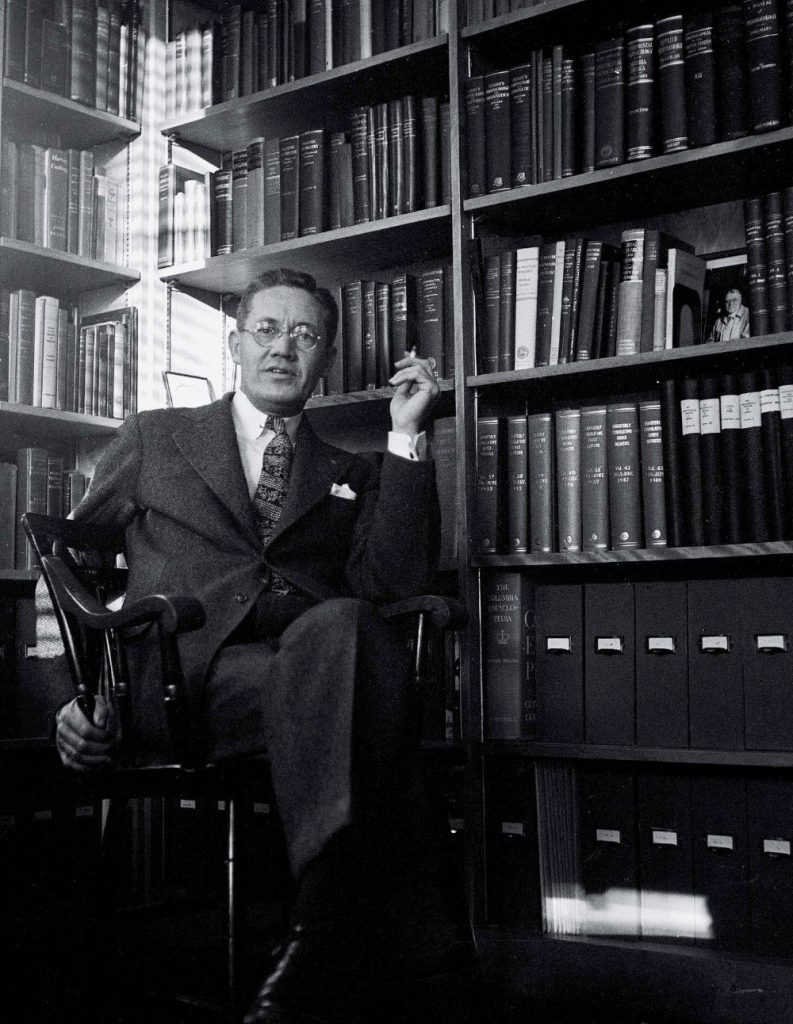

Henry Knowles Beecher was a pioneering American anesthesiologist, placebo effect researcher, and medical ethics specialist. Due to his somewhat controversial character—breaking barriers and revolutionizing everything around him—we're certain he would have been part of the Sedalux team.

Raised in rural Kansas during World War I, he changed his German surname to the Anglophone Beecher in the 1920s and traveled east to earn his medical degree at Harvard. During World War II, he conducted influential research on pain, bringing the issue of placebos to the forefront of discussions about how to properly design clinical trials.

He took notes on his observations during the combat at the beaches of Anzio and the horrors of Monte Cassino, where he continued describing pain and resuscitation while fulfilling his duties in the war—experiences that would inspire his future work. This later allowed him to propose the hypothesis that pain had two aspects: the actual tissue injury and the personal meaning of that pain for the individual. He was ahead of his time in understanding the difference between nociception and pain (or painful experience), as well as the complexities of our psyche in pain processing.

In his study on the impact of pain in soldiers, he observed that wounded soldiers requested pain medication less frequently than civilians with similar injuries. His explanation was that the consequence of the painful experience was different for soldiers than for civilians. For a soldier, a serious wound could mean being relieved from combat, whereas for a civilian, a wound meant personal inconvenience, loss of time, and money (Beecher, 1945).

Between the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War, Beecher was funded by the Office of the Army Surgeon General with $150,000 to investigate “The development and application of drugs that would assist in the establishment of psychological control.” He became involved in experiments with lysergic acid (LSD), secobarbital, amphetamines, and meperidine. He was heavily criticized, despite the fact that his work on the effects of LSD was consistent with the research line he had started during the war. We should also consider that until 1960, LSD was a legal drug approved for use, and Beecher’s work was published about a decade earlier. Furthermore, the drug was not yet considered a hallucinogen, but rather had “psychotomimetic” effects.

He was accused of double standards for conducting LSD research with military funding, but his writings reflect his genuine concern for understanding higher brain functions and the effects of drugs (which, at the time, had not yet been extensively developed or linked to specific pathologies and behaviors). As a person of integrity and transparency, he acknowledged the mistakes in the studies he participated in and consistently sought to ensure others would not repeat them.

In addition to raising concerns about clinical safety in anesthetic practice, in 1968 he led a Harvard working group to examine the definition of “brain death”, which established influential and controversial standards that allowed doctors to disconnect patients from life support. This was the first consensus on brain death criteria: the so-called “Harvard Criteria.”

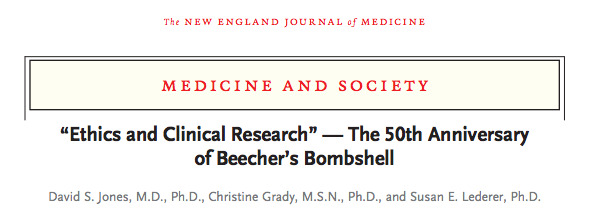

But what made him truly remembered was his article “Ethics and Clinical Research” published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in 1966, in which he sought to highlight a weakness in research ethics. He exposed 22 studies that violated human rights, sparking and embedding in the scientific community a necessary debate about the scope and limits of medical ethics—and how to assess the harm caused by exposing human beings to “experiments.” His work was fundamental to the implementation of federal regulations on human experimentation and informed consent.

Beecher inspired the current landscape of health research. His life was marked by profound contradictions and tensions between ethical and unethical, legitimate and illegitimate, legal and illegal, right and wrong, doubt and certainty. Nevertheless, he was an anesthesiologist ahead of his time, envisioning that the most tangible and practical expression of ethics is “integrity” in research.